Landstar Systems (“$LSTR”) is a multi-sided platform technology business. It connects 1,200 independent sales agents, 79,000+ truck capacity providers, and 25,000+ customers. This is an extremely good business with terrific financial metrics, even though competition in its subsector, truckload, is intense due to extreme fragmentation (see Heartland Express deep dive).

The distinguishing factors that make $LSTR, and truck brokerage companies more generally, attractive businesses are:

Very high returns on capital because of low asset intensity

Moderately increasing returns to scale

Landstar primarily operates in the extremely competitive for-hire truckload subsector, which we covered in some detail last month as part of the $HTLD writeup. $LSTR does have some other businesses, with a bit of rail intermodal and air and ocean forwarding, but these are collectively less than 10% of revenues so we will hold off the analysis on these for now (I cover these sectors briefly in my industry overview piece for curious minds).

$LSTR is part of a category of freight transportation called “truck brokers.” A decent analogy would be that these are matchmakers, but instead of matching couples for love, they match shippers with freight to ship with carriers to move stuff. Truck brokers don’t actually own/lease the power equipment and only sometimes own/lease the trailers. While they still have to compete aggressively to provide competitive rates to customers, the asset-light aspect of the business means that with a thoughtful business strategy they can scale very nicely without much need for additional capital. Moreover, as supply chains have gotten “leaner,” there’s been a long term secular trend of requiring more flexible transportation (vs. fixed routine routes) which brokers are better able to service vs. asset-based carriers.

On to $LSTR. The key concept to grasp for $LSTR is that despite cut-throat competition in the truckload subsector, it is possible to create businesses that rise above the challenges of the industry. Namely, while there isn’t material scale advantages going from owning and operating 1 truck to 10 trucks to 1,000 trucks (and beyond), there are scale advantages if you avoid investing in trucks altogether, dedicate time to provide knowledge and a service, and build a massive multi-sided technology platform. As we covered in the industry overview, truck brokers are exactly that, service as matchmakers pairing shippers with carriers.

$LSTR’s further twist on this is that they also outsource the matchmaker function to contractors who work directly with the shippers and carriers using $LSTR’s technology and services platform. This schema illustrates $LSTR’s business pretty well, $LSTR directly controls the middle while all the other parts are external parties:

$LSTR’s business is very asset light, and generates very strong returns on capital with low levels of capex (net revenue is a non-GAAP industry metric defined as total revenues minus purchased transportation):

However, over time the return metrics have been trending lower ever so slightly. This is the difference between $LSTR and $ODFL. $LSTR’s return metrics are superior, but its competive advantage isn’t as strong and competition has been increasing over time. $ODFL on the other hand has inferior financial metrics mostly driven by higher capex needs, but the high capex combined with strong increasing returns to scale leads to the winner-takes-most dynamics and deters new entrants (see the deep dive on $ODFL).

Let’s take a deeper look at the business. This is how a typical shipment is handled in $LSTR’s system:

The engine that makes this go is the independent sales agent: they are effectively franchisees of $LSTR’s technology and services. Most sales agents generally work exclusively with $LSTR. They own the customer relationship, and they also interface with the truck provider. If something goes wrong with a shipment, the sales agent is responsible for fixing the problem.

A few more facts about the independent sales agents:

There’s about 500-600 agents that help generate $1M+ in revenue for $LSTR (“Million Dollar Agents”). This is close to half of all agents (1,200).

Million Dollar Agent attrition is under 3% annually. In 2020, there were 0% attrition in agents who generate over $5M in revenues in 2019.

Million Dollar Agents average $7.5M/agent in revenues.

Million Dollar Agents account for about 93% of $LSTR’s total revenues historically.

As you can see, sales agents that generate the bulk of the revenues are a pretty sticky group. This has been a nice driver of long term growth, with Million Dollar Agents growing at about 2%/yr CAGR and revenues/Million Dollar Agent growing 4%/yr, combining to around 6% revenue growth overall.

The other unique aspect about $LSTR’s business is that they also have agreements with truck owner operators who exclusively drive for $LSTR in addition to securing completely independent third party trucking capacity. These exclusive carriers are called “BCO Independent Contractors” (or “BCOs”), which contrasts with carriers that work for any broker or shipper that we define as “Truck Brokerage Carrier”. BCOs bring their own power equipment, and sometimes brings their own trailers as well. Here’s the cost/benefit from the perspective of BCOs as well as $LSTR:

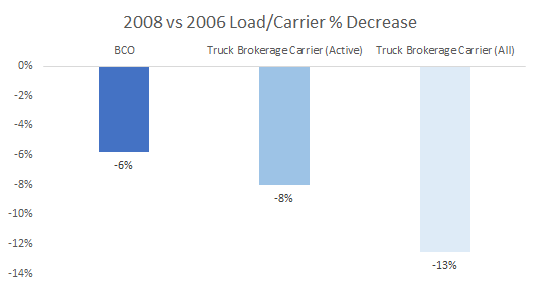

The benefit from steadier freight could be seen in the chart below, which shows number of loads hauled per carrier across each type of carrier in the recession of 2008 vs headier times in 2006. You can see that BCO volumes saw a significantly less intense decrease in loads/carrier vs. carriers that have a brokerage relationship with $LSTR:

And the benefit to the BCOs can be seen in lower driver churn: $LSTR’s BCO turnover is about 25-35% annually, vs. the asset-based truckload industry at 80-100%.

BCO counts have seen consistent growth over time, more or less keeping pace with independent sales agent growth. However, the interesting thing is that $LSTR’s growth actually is driven by growth in Truck Brokerage Carriers. In 2001, BCOs accounted for 75% of $LSTR’s revenues, but by 2020, BCOs only account for 45%.

So the story here seems to be that $LSTR originally built out a committed, exclusive truck carrier base. As time went on and the platform matured, $LSTR added more and more non-committed third-party capacity, which is ultimately what’s been driving much of the growth over time as revenues have grown by 6%/yr CAGR since both 2001 and over the last 10 years. But remember again the driving factor here, especially with respect to Truck Brokerage Carriers, is that the independent sales agents have been diligently growing their own businesses.

I think what we can infer from this is that future growth here will come from:

Independent Sales Agent and BCO growth at ~GDP

Growth in revenues per sales agent from adding more truck brokerage carriers

New products

Let’s talk briefly about new products. $LSTR continues to tinker with adding additional services for sales agents to help customers. There’s three specific ones I’d like to flag:

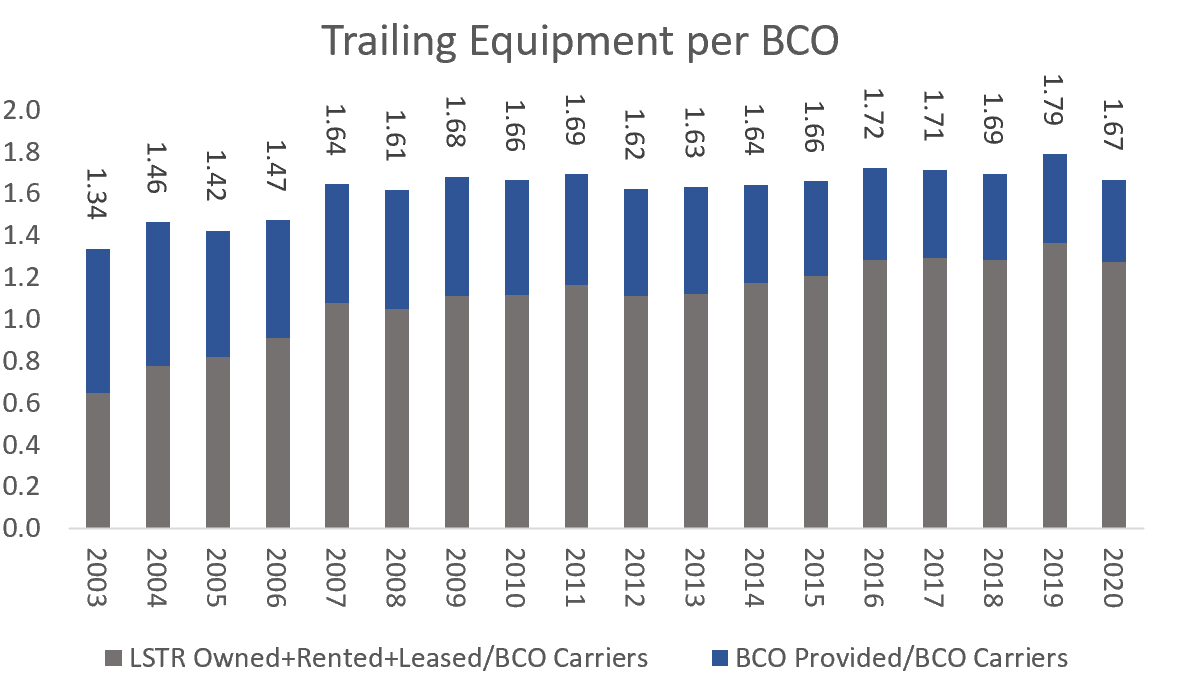

Drop and Hook: If you read industry publications, there’s been a persistent, long-standing concern about a truck driver shortage. While this calmed down a bit as the transports world was overcapacity for a stretch of time, it’s come back into sharp focus with the COVID-driven demand boom (that feels really weird typing that out…). One solution to fix this lies in the insight that a lot of time is spent loading/unloading trailers. To save the driver’s time, it’s possible to order a few more trailers than tractors/drivers and then preloading the trailer/unloading the trailer without the driver present. Hence, “drop and hook.” You can see the impact of this in the increase in trailers per BCO carrier, it has steadily increased. 2015 was the first instance that $LSTR disclosed “drop-and-hook” specifically in the 10-K, and trailing equipment per BCO appears to continue to edge higher.

Committed Contractual Freight: Historically $LSTR is a “spot” market player, meaning they largely helped customers book freight on an ad hoc basis. The key insight is that there exist shippers out there who may be interested in dealing with $LSTR on a more commited, contractual basis (which $CHRW has been a leading player, we’ll likely cover $CHRW has a reasonably large freight forwarding business in addition to truck brokerage). Basically, instead of contracting with a trucking company with company drivers and equipment, the shipper would contract with $LSTR as an aggregator for all the independent small truck drivers out there.

Digital Initiatives: $LSTR continues to work on improving their technology functionality. 2021 projects include:

Investing further in Landstar Blue, which tests new technologies that can be used to support pursuing more committed freight as described in the point immediately above.

Automating arrangement of 13K trailing equipment, which should support the Drop and Hook initiative.

Third party truck brokerage tracking, similar to what’s already being done with BCOs.

Now to address the elephant in the room: disruption. It is my loosely held opinion that disruption is difficult in this sector. This is despite the quite clever slogan: “Uber for trucking,” which was catchy enough to even convince Uber to launch an Uber Freight subsidiary. The issue with that is that passengers and freight are pretty different and so what works with passengers probably won’t work with freight:

Taxis were a fragmented industry whose profitability largely depended on regulatory capture (historically you needed a license from a city to operate a taxi, and these can be pretty steep). Hence, legacy providers on the aggregate lived comfortably and innovation slowed dramatically and there wasn’t any centralized services providers aggressively working to make the industry more efficient. Trucking is already fairly competitive with quite a few service providers consistently trying to make the industry more efficient.

Trucking movements are “unbalanced”. Meaning, there are persistent flows out of certain locations (e.g.: Los Angeles, Chicago) and into others since U.S. imports outweigh exports. Passenger movement is also unbalanced, but in a different manner. For example, pre-COVID rush hour sees more people going into cities than out in the morning and the opposite in the evening. However the difference is that trucks drive much longer distances, so a truck driver is far more likely to get “stuck” somewhere very far from home without a backhaul home if they’re not careful.

The distance also makes it tougher to just trust the technology. If you’re a shipper and you booked a truck on a tight schedule, it’s very hard not to try to call to confirm the truck is on its way. Similarly, if your a truck driver and someone requested a truck, it’s tough not to call before driving 100 miles one way to pick up a load.

While disruption is and always will be a concern, I don’t think the latest round of challenges is anything new. In my view, the strongest incumbents such as $LSTR will continue to do well, although like in most marketplaces (e.g.: discount securities brokerages), gross margins if not operating margins should compress over the long term.

As mentioned in the previous section, $LSTR also spends quite a bit in research and development as well (plan is for $18M in 2021). Admittedly, though, their systems are old. $LSTR is currently in the midst of rolling off their 1980s IBM-based transportation management system onto a new, more flexible Transportation Management System, with an eye towards rolling this out to 80% of agents in 2021.

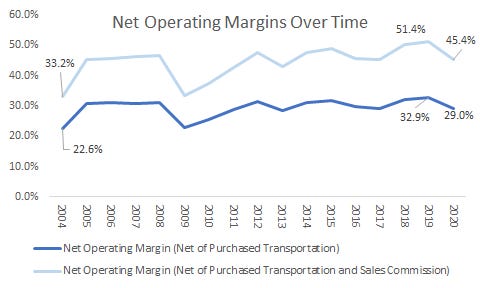

The bigger concern should really be competition overall. As inferred above, return on capital metrics have drifted lower over time. This is because competition has increased. The preferred metric for transportation insiders in evaluating truck brokers is “net revenues” which is revenues less purchased transportation costs. In effect, this non-GAAP metric basically says that similarly to a securities broker, we shouldn’t include the total dollar amount traded by a client as “revenues” since ultimately the truck broker is providing a service and outsourcing the transportation piece to a third party. And as you can see, the margins do seem to trend downwards over time:

It’s important to note two biases in the data that skews the broader picture:

Margin deterioration is overstated because truck brokerage has lower net revenue margins so with that segment becoming an ever-larger component of $LSTR’s revenues there’s a mix issue.

Net revenue margins for truck brokerage is gross of fuel, so in low fuel environments (such as today), net revenue margins are overstated because both the numerator and denominator are smaller by the same absolute dollar amount.

Thankfully, despite the pressure on net revenues, $LSTR platform business has decent scale advantages which allows net operating margins (defined as operating income divided by net revenues) to be flat to higher over time. Most incredibly, $LSTR’s employee count at the end of 2020 (1,320) is a mere 70 heads higher than its employee count in 2004 (1,251).

So to summarize, $LSTR has an excellent franchise-like platform business despite operating in the extremely tough truckload subsector. It has really, really high returns on capital. Unfortunately, the business is a bit too good, and thus competition continues to intensify and net revenue margins and returns on capital are slowly drifting down, from incredible to…still incredible. Disruption is certainly a risk, and $LSTR has some old systems but they continue to invest in technology themselves. $LSTR should continue to grow as they continue to add services to their business. The business itself is actually superior to $ODFL, but the key difference is that while $ODFL’s advantage continues to consistently grow over time, $LSTR’s appears to be slowly shrinking.

Disclosure: No position in $LSTR or $HTLD or any other named stocks with the exception of $ODFL.

APPENDIX

Truck brokers work with shippers under two types of arrangements, spot and contractual agreements:

Spot: Generally isn’t a commited price and/or volume from the shipper, shipper looks for carrier capacity on an ad hoc basis.

Contractual: Truck broker agrees to provide capacity, generally at an agreed upon price and volume.

In practice these definitions can be blurred a bit depending on the agreement. But generally the former is more volatile and is used by shippers solving for “unplanned freight” (examples: we had one more truckload than expected needed to move to our stores, we need to service a special event in Chicago, our supply chain broke due to the Suez Canal and now we need emergency inventory shipped from our secondary supply source). The latter is generally more of a substitute for working with an asset-based carrier (e.g.: $KNX or $HTLD), introducing the truck broker as a middleman to leverage their wide carrier network to provide a more consistent, regular service.

The way you explain a complex topic in an easy-to-understand way is really impressive.